(Originally published April 2016 in Plant Science Today)

Recently, I was asked it if is ethical to give a job to a woman rather than to a man of higher quality. I replied, “How do we measure “quality”? This is the longer answer that I didn’t have time to provide.

Achievement does not equal quality

Imagining that we can measure a scientist’s “quality” from their publications list completely ignores the inequalities of the society in which science is embedded.

Consider this:

“Educational attainment is a function of access, information, motivation, affordability, academic preparation and support, social support and integration, and professional development.”1.

In other words, a white man who attended a good high school and was raised in a family of university-educated parents has an easier path to academic achievement than someone with a different demographic profile. Educational achievement is crucially dependent on social status as well as intellectual ability.

There is an inherent social drag associated with being an “outsider”. Outsider status is felt by many scientists, and can stem from gender, race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, disability, sexual orientation or other factors. This social drag can be experienced as harassment, discrimination, bias, or isolation (see for examples Handelsman et al 2005, Moss-Racusin et al, 2012, Shetlzer and Smith, 2014 and references therein). [Note that outsider and insider status are defined by tradition; the geographer William Smith was denied recognition for his work because he came from the wrong social class, and men working in historically female professions such as nursing or primary education regularly experience gender discrimination. For more on what diversity is and isn’t, see Gibbs, 2014 “Diversity in STEM and why it matters”.]

To read that 63 – 77% of women report “having to provide more evidence of competence to prove themselves” or that 48% of black women report that they’ve been “mistaken for administrative or custodial staff” is one thing, but personal stories bring the true impact of these statistics to life (Williams, 2015). If you have any doubt that the constant need to defend oneself against bias and to justify one’s worth detracts from the pursuit of science, I urge you to seek out and listen to the experiences of women and minority scientists. (As examples, see the writing of D.N. Lee including her excellent article “Engaging minority scholars in science should also include addressing isolation and mental wellness”, and watch Jedidah Isler’s TED talk “The untapped genius that could change science for the better”) .

When we recognize that social status, gender and race affect access and acceptance within the scientific community, how can we imagine that a CV tells the whole story of someone’s “quality”?

Culture affects achievement

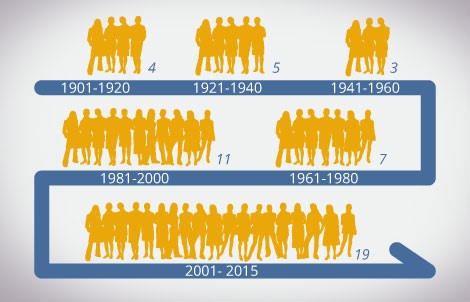

The number of women who won Nobel Prizes increased from four between 1901 – 1920, five between 1921 – 1940, three between 1941 – 1960, seven between 1961 – 1980, 11 between 1981 – 2000, to 19 between 2001 – 2015. What happened, did women suddenly get smarter or more talented? Of course not; the culture changed, providing greater opportunities for women to contribute their talents. As the culture of science became more accepting to women, women participated and achieved more (for more on this, see Pollack’s 2013 article, “Why are there still so few women in science?”). Opportunities for women and underrepresented minority scientists have increased since the beginning of the 20th century, but challenges remain.

Increasing diversity also leads directly to greater achievements in science. Problem solving, creativity and innovation benefit from diverse groups (see for example Hong and Page, 2004, Phillips, 2014 and Gates, 2016).

Creating a culture of inclusion

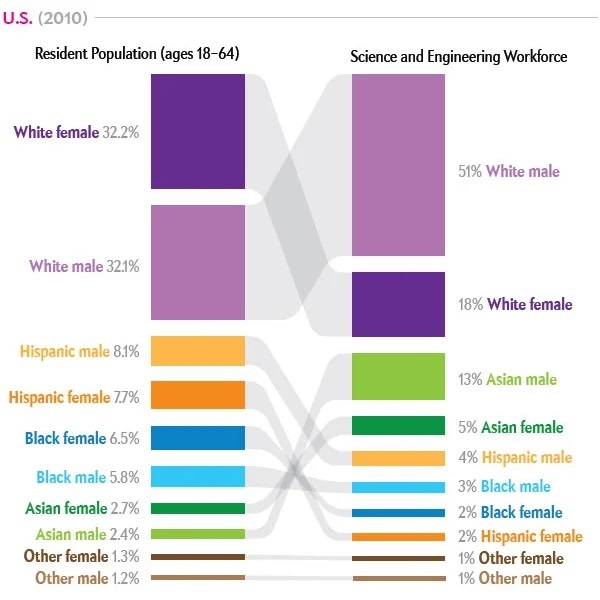

The science and engineering workforce does not reflect society’s demographics, as shown by data for the US from 2010 (Guterl, 2014). The US workforce “remains woefully underrepresented in Hispanics, African-Americans, and Native Americans compared with the U.S. population. The inescapable conclusion is that we are missing critical contributors to our talent pool,” (Tabak and Collins, 2011).

Without intervention, this disparity will self-perpetuate, as women and underrepresented minorities (and other “outsiders”) continue to experience science as a place that excludes them. Addressing science’s inequities involves cultural changes in society at large and within science itself.

“Diversity is not about filling a quota; it’s about creating a system in which all talents have an opportunity to rise and different perspectives are encouraged rather than suppressed.”2

Creating a scientific culture of inclusion requires a commitment from all stakeholders. The types of actions are varied. Some occur at an institutional level, such as making diversity training available for all, and providing flexibility in work scheduling for parents (see Williams, 2015 and Williams et al., 2014). Educating search and selection committees about how to overcome the effects of implicit bias can be an important step towards increasing diversity (Smith et al., 2015). The institutional commitment should be codified through a public statement in support of inclusion and diversity (see examples from the Royal Society of Chemistry and Leiden University).

Every position or opportunity has a social aspect. Professors teach, mentor, serve on committees and grant review panels, and appear on university websites. Conference speakers are featured in conference programs and provide models of high-achievement to inspire other scientists. Impact on diversity should be considered when identifying candidates for such positions. Having a diverse organizing committee maximizes your chances of identifying and attracting a diverse speaker pool (see Martin’s 2014 article, “Ten simple steps to achieving conference speaker gender balance”). Word-of-mouth efforts and judicious placement can ensure that job ads reach women and underrepresented minorities, maximizing your chances of a diverse applicant pool.

Increasing the diversity of an organization or department can lead to a more welcoming and inclusive environment that will attract and retain a more diverse workforce. Retention is often cited as an explanation for why women are underrepresented at the highest levels of academia, with parental duties as a contributing factor to women’s attrition (Williams, 2015). Who implements programs to provide flexibility for family care? Usually women. When I was a pregnant Assistant Professor and approached my Dean to discuss my leave, there were no provisions for faculty maternity leave as it had “never been an issue”. Needless to say, a system was soon put into place.

Individual scientists can contribute to a culture of inclusion by using gender neutral language, providing diverse examples of scientists when teaching, inviting underrepresented minority speakers to campus, and joining an allies program to support LGBTQ+ scientists and students. You can explore other ways to become more aware of the issues surrounding diversity and inclusion in science, such as the diversity journal club’s biweekly online discussion series, or by following Twitter accounts set up to discuss diversity such as @BLACKandSTEM, @ABRCMS, @MinorityPostdoc and @SACNAS. Nature and Scientific American have assembled an excellent collection of articles about increasing diversity in science here.

Reaching out

Providing equal access to careers in science is an immense challenge that is being systematically addressed through a variety of programs, starting with increasing children’s access to science (Johnson and Okoro, 2016). Holistic support to minority students as they transition to university and beyond is the focus of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program developed at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (see Gewin 2014). The British Royal Society also supports a wide range of programs to support diversity in science, and the National Institute of Health is systematically addressing diversity in the biomedical workforce (Valentine and Collins, 2015). Proposals to remedy educational inequalities are also being explored and implemented by the National Academies as put forth in the 2011 report, “Expanding underrepresented minority participation: America’s science and technology talent at the crossroads”.

Diversity in plant biology

The ASPB has a commitment to increasing diversity and establishing a climate of inclusiveness, which you can read about in the ASPB’s Position Statement on Diversity. ASPB supports this commitment through a variety of efforts, including the efforts of the Women in Plant Biology Committee, Minority Affairs Committee, and International Committee. These committees host speakers, run workshops, provide travel awards and promote networking and mentoring (see Plant Biology 2016). In a recent article in the March-April issue of the ASPB Newsletter, Minority Affairs Committee members Beronda Montgomery and Adán Colón-Carmora describe ASPB’s partnership with the National Research Mentoring Network https://nrmnet.net/.

ASPB’s educational efforts also contribute to broadening access to science, from its participation in PlantingScience.org, reaching out to teachers at science teacher conferences such as NABT and NSTA, and providing quality materials for use in K-12 and higher education classrooms. Plantae.org provides opportunities such as the Women in Plant Biology discussion group for plant scientists to network and discuss important but challenging issues.

Plant biology and science more broadly must fully draw upon and support society’s talent pool. Towards this end, we must recognize that historical practices have contributed to skewed demographic representation in sciences and make a commitment to redressing these inequalities and broadening participation in science. Instrumental to these efforts is recognizing the fact that striving for excellence and striving for diversity are not incompatible.

- National Academies, 2011.

- Quote from Johnson and Okoro, 2016.

References

Gates, S.J. (2016). Einstein v. Roberts. Science 351: 1371.

Gewin, V. (2014). Diversity: Equal access. Nature 511: 499-500.

Gibbs, K. (2014). Diversity in STEM and why it matters. Scientific American.

Gill, J. (2016). Ten easy ways you can support diversity in academia in 2016.

Guterl, F (2014). Diversity in science: Where are the data? Scientific American.

Handelsman, J., Cantor, N., Carnes, M., Denton, D., Fine, E., Grosz, B., Hinshaw, V., Marrett, C., Rosser, S., Shalala, D.,.and Sheridan, J. (2005). More women in science. Science 309: 1190-1191.

Hong, L., and Page, S.E. (2004). Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 16385-16389.

Johnson, A., and Okoro, M.H. (2016). How to recruit and retain underrepresented minorities. American Scientist, 104: 76–81.

Lee, D.N. (2016).Engaging minority scholars in science should also include addressing isolation and mental wellness. Scientific American.

Martin, J.L. (2014) Ten simple rules to achieve conference speaker gender balance. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003903.

Moss-Racusin, C.A., Dovidio, J.F., Brescoll, V.L., Graham M.J., and Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 16474-16479.

National Academies Press (2011) Expanding Underrepresented Minority Participation: America’s Science and Technology Talent at the Crossroads. National Academies Press (available online).

Phillips, K.W. (2014).How diversity makes us smarter. Scientific American.

Pollack, E. (2013). Why are there still so few women in science? New York Times Magazine.

Sheltzer J.M. and Smith, J.C. (2014). Elite male faculty in the life sciences employ fewer women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 10107-10112.

Smith, J.L., Handley, I.M., Zale, A.V., Rushing, S,. and Potvin, M.A. (2015). Now hiring! Empirically testing a three-step intervention to increase faculty gender diversity in STEM. BioScience 65: 1084-1087.

Tabak, L.A. and Collins, F.S. (2011). Weaving a richer tapestry in biomedical science. Science 333: 940-941.

Valantine, H.A .and Collins, F.S. (2015). National Institutes of Health addresses the science of diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 12240-12242.

Williams, J. (2015). The 5 biases pushing women out of STEM. Harvard Business Review.

Williams, J.C., Phillips, K.W., and Hall, E.V. (2014). Double Jeopardy? Gender bias against women of color in science. Tools for Change, Work Life Law.